Philosophical Examples Illustrating The Conflict Between Subjective And Objective

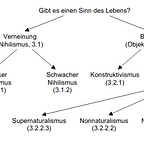

One of them is “the meaning of life”.

--

When I first read Nagel’s work, I got a bit frustrated with how the philosopher expounds on the problem. Or rather, how he doesn’t (at first).

Thomas Nagel (born 1937) discusses in his work “Subjective and Objective”, how one common problem goes through various fields of philosophy. The reason for this problem is the difference between subjective and objective points of view.

After a short introduction he clearly states that he won’t discuss the problem already in the beginning, and neither explain what the terms subjective and objective mean exactly.

Instead, he presents five examples from the metaphysics and ethics through which he wants to illustrate the issue.

1. The Meaning of Life

Nagel blatantly starts with this topic and perpetuates the stereotype of a philosophical text (this was actually one of the first texts we read when I began studying philosophy at university). But he explains why the meaning of life fits well in his problem of subjective and objective.

In summary, here’s what he states: If one tries to look at his life objectively, he’ll see that it is meaningless. Hence it is absurd that humans are trying to find some meaning in their lives, when at the same time, they are capable of viewing it from an external perspective and that it is meaningless.

Still, it makes sense that I try to see meaning in my life because that’s how I usually live my life: From a personal, inner perspective. So it is indifferent that my life seems insignificant from an external point of view.

He concludes that we still strive for viewing things objectively because it seems as if it is the only right way to see how things are for real — and we want to know the truth, it’s what we highly value. We want to get out of our own falsifying and limiting viewpoint.

2. Free Will

This topic is a bit more complicated, I’d say. Nagel speaks about terms like determinism and how it impacts our actions.

Determinism is a belief in philosophy that all events are determined by causes which have previously existed.

Is there a freedom to act? Actions that I didn’t cause could hardly be attributed to my person. And maybe also events that were caused by prior circumstances.

The author states that the problem with determinism is that it leaves no room for the actual acting. But the problem without determinism remains the same: If an event isn’t causally linked to other events, we see that there is no room for acting, either.

Some philosophers have set the agent as the cause instead of prior events. But it doesn’t work like this, Nagel states, because here again we can see no real acting, but only a causal chain.

From an external point of view, there’s only a chain of events. From a personal viewpoint, objectivity leaves out that it is my acting, no matter if it is deterministic or not. The person sees their actions as fundamentally different than other events that happen somehow. The same is for actions committed by other people: They seem as they aren’t really happening to that specific person.

The ethical problem here is: If we see our actions and those of others just as an event among other events, we leave out the question of responsibility and guilt.

3. Personal Identity

This problem is about personal experiences and how one could think of its “past self”.

Is one now the same person as yesterday? Is it my future experience? Can we speak of the same self, the same subject over time?

Nagel speaks of it as “the same self as this one”.

The internal idea a person has from themselves is different from the picture we get if looked at the person from an outside perspective. Objectively, a person persists as a thing in this world as time passes. But only the subject can see the self, and from an external viewpoint, it is left out. From this derives the problem of personal identity.

4. The Mind-Body Problem

Objectively, you can physically describe how a person is and how they behave through stimuli.

But what one can’t display objectively is the subjective experiencing. How is it to live for a living being, to experience certain stimuli?

It’s impossible to physically characterize, Nagel argues, how it actually is for a person to live in physical circumstances. We can observe that one individual is there in the world, in different conditions. What we leave out are the subjective aspects of being physically (which can be seen only by the individuals themselves, or maybe another, very empathetic person).

There are a lot of problems and questions associated with that, the relation of body and soul, personal and impersonal/subjective and objective, or the question of dualism:

How can a mental substance with subjective properties be in an objective world, or how can a physical substance have subjective properties?

5. Utilitarianism vs. Deontology

Utilitarianism is an ethical theory that says the consequences of an act determine the moral value of the act. Critics often argue that it leaves no room for the agents to think about their personal lives and how they want to live it, but they must always consider whether their action has a greater meaning regarding the majority of the people.

As utilitarianism demands, the sum of the preferences of many people is the most important and worth striving for. Then, Nagel argues, it’s impersonal and completely independent from the individual’s viewpoint, his wishes and goals for life. Therefore, it is objective.

Naturally, if one looks at it from an individual viewpoint, it seems bizarre. One might not be happy with the idea that his actions should serve completely the highest aim and leave out its own interests.

Deontology, which judges the action by the adherence to a set of rules, can be seen as subjective, and the single person has more value. The reason for it is that there is not one single goal (as in utilitarianism) which an agent needs to keep in mind whenever that person acts.

Constraints against murder, betrayal, etc. are subjective, but not in the sense that the agent is considered as the subject, but the potential victim whose rights should be protected.

The big problem here (and generally, in philosophy) is which one, utilitarianism or deontology, to consider when it comes to acting.

To Sum up

Both subjective and objective claim to see the bigger picture: The impersonal sees the whole world and excludes the personal view of the individual, and for one individual, the entire world is just one concern out of many in his life.

I still ask myself: Why do we desperately strive for objectivity, if in the end it leaves us unsatisfied and feeling as if it lacks something important (the subjective component, obviously).

Nagel argues that objectivity is connected inevitably with reality. He says:

“It is easy to feel that anything has to be located in the objective world in order to qualify as real”

Do we really want to be able to see things objectively? What if everything would appear cruel and meaningless? And what if we could never return fully to our personal view but we would always have this “other” viewpoint in the back of our minds?

Maybe we won’t ever know, because it’s difficult to see and evaluate things not only independently from our understanding of the world, but also our characteristics as a species, our human perspective.